MASTERS THESIS: Gowanus Outdoors Club: A Field Guide to Soliphilia, by Julia Plevin

Design strategist and storyteller Julia Plevin did not realize how much of an effect the environment had on her wellbeing before she moved to New York City to attend the Products of Design program and found herself yearning for nature. But after a harsh New York City winter left her depressed and out of whack, she realized that she suffered from Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD).

And she realized she was not alone. According to the National Institute of Health, 6% of the U.S. population suffers from seasonal affective disorder and 14% of the U.S. population suffers from winter blues. These numbers are even larger if you consider that many Americans live in places—like California or Florida—that do not have long, cold winters.

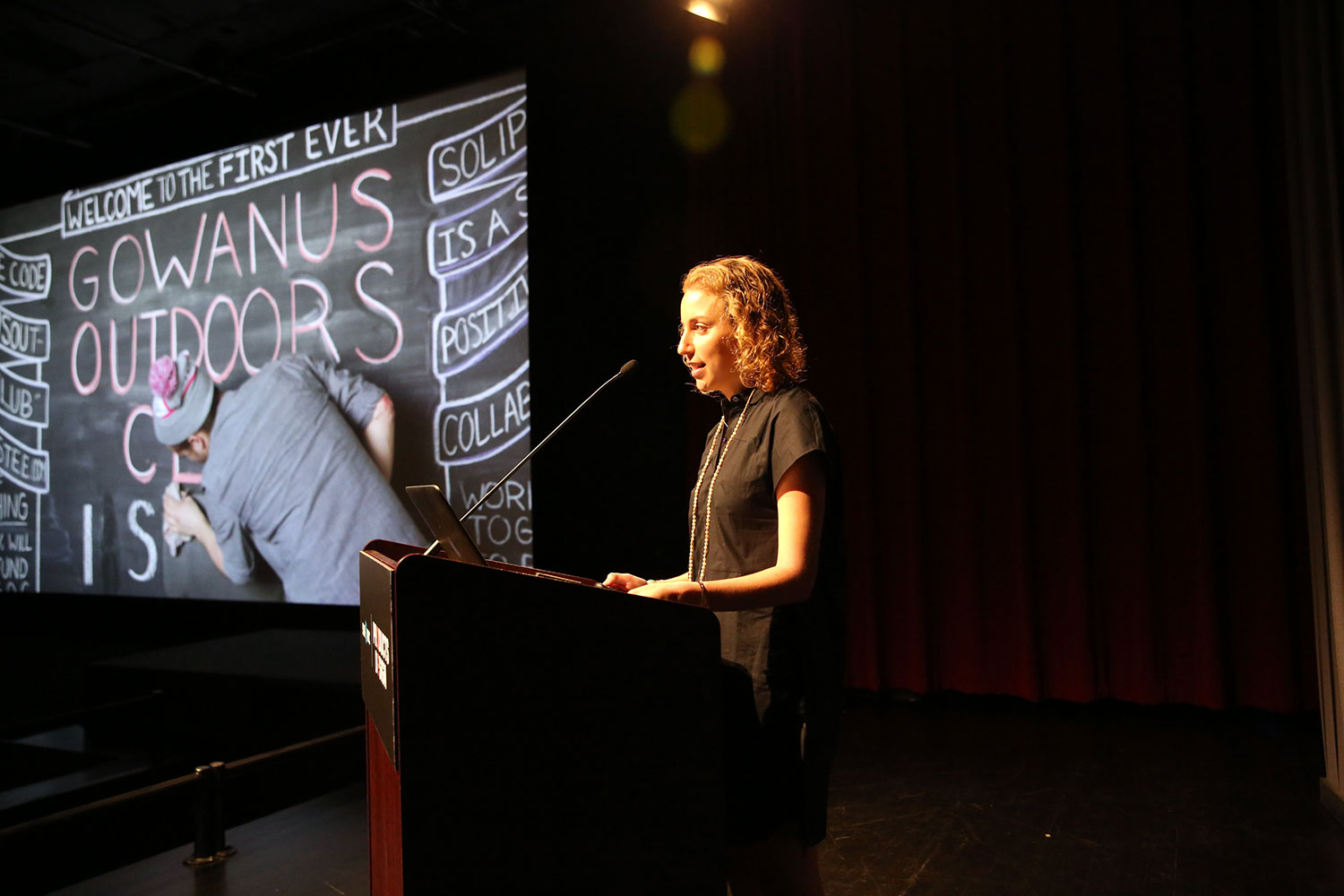

Watch Plevin's live thesis presentation and Q&A below:

Psychologists and scientists are realizing the impact the environment has on mental health. Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined the term psychoterratica, to encompass the whole set of earth-related mental health disorders.

Seasonal Affective Disorder is in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which is to psychologists what building code is to architects. What surprised Julia most is that SAD is the only nature-related disorder in the DSM.

As the late scholar Theodore Roszak wrote in an article for Psychology Today, “Psychotherapists have exhaustively analyzed every form of dysfunctional family and social relations, but ‘dysfunctional environmental relations’ does not even exist as a concept.”

However, as Julia was excited to discover, this is all about to change. Psychologists and scientists are realizing the impact the environment has on mental health. Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined the term psychoterratica, to encompass the whole set of earth-related mental health disorders.

Some of these disorders are: nature deficit disorder, generational environmental amnesia, solastalgia, eco-anxiety, global dread, eco-paralysis, and eco-phobia. Julia found that these sentiments resonated with people, but that they had never heard of the terms. So her challenge became how to help people realize the impact the environment has on their mental health, and ultimately to create ways to help people reconnect with nature.

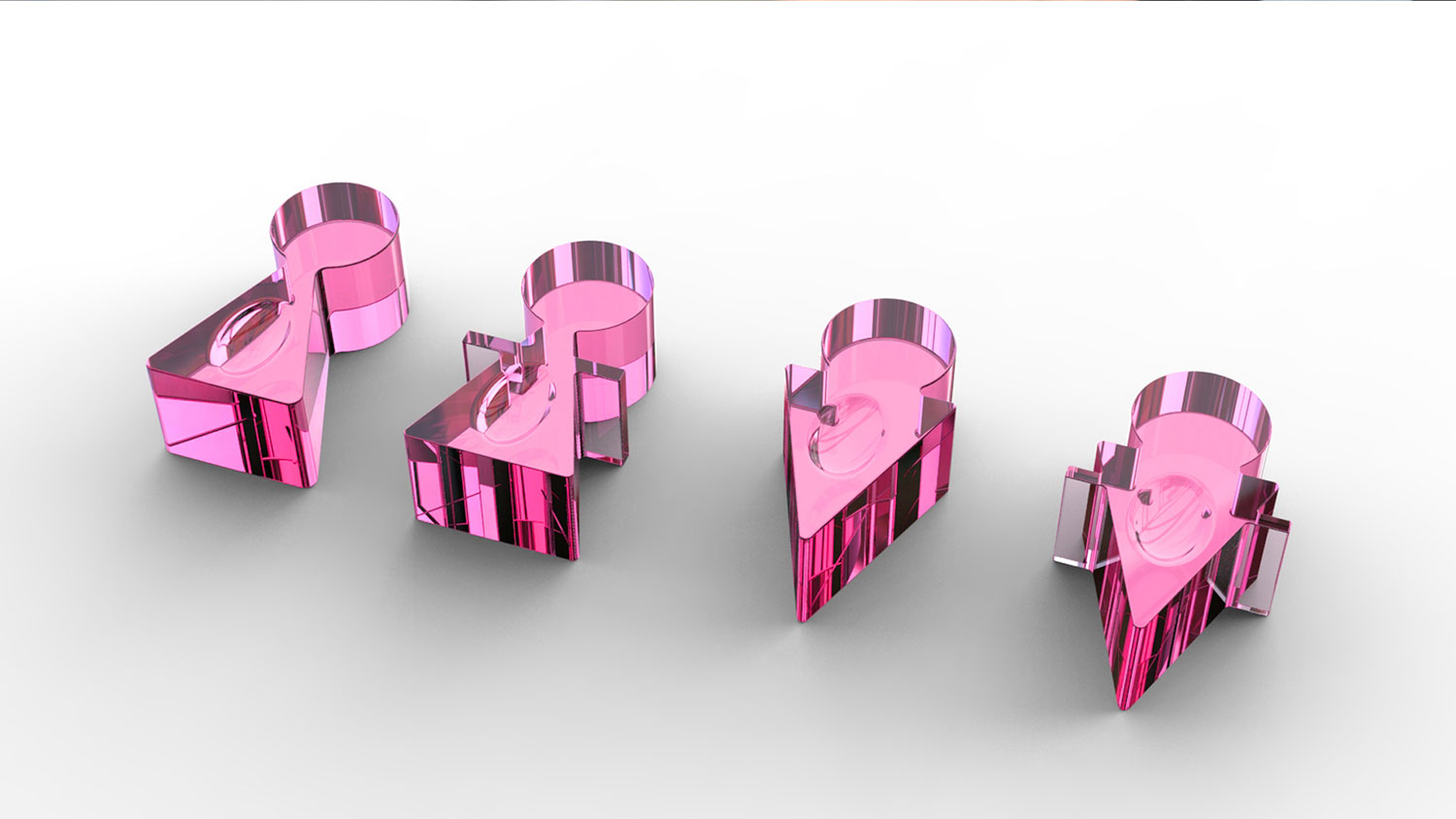

Environ-mental Worry Dolls

Inspired by a long tradition of worry-relieving products from cultures around the world (such as worry beads and worry stones), Julia created the concept for Environ-mental Worry Dolls for people who feel eco-anxiety, eco-paralysis, or global dread. She brought these environmental worries to life, so that we can talk about them and start to act on them.

Plevin wanted the dolls to have as little of an environmental footprint as possible of course, so she experimented with growing material from kombucha. "Kombucha mothers" take the shape of their container, so by designing a doll shaped container, she was able to grow dolls.

Julia then speculated on how therapists might treat patients in a future scenario—when psychoterratic distress is included in the DSM.

In this future, an esteemed New York City psychologist has begun making molds for all her clients who are distressed, anxious, and depressed about the environment.

These molds are of all of things that are disappearing with climate change—such as the Joshua Trees, salmon, coral, and a sacred glacier in Peru—serving as transitional objects for patients. The patients are then prescribed "missions," such as bringing ice in the shape of the Qolqepunku glacier back to Peru. The glacier is melting fast, and the locals believe that "when the ice melts, the world will end."

In a more mass-manufactured embodiment, the shape of the dolls are inspired by the alchemy symbols for Earth, Wind, Fire, and Water.

The Terrarium isn’t meant to replace nature, but rather be a supplement to it. As Jonathan Kaplan, Ph.D. writes, “Having plants, going for a walk in the park, or even looking at a landscape poster can produce psychological benefits, reduce stress, and improve concentration.”

Terrarium

For people who don’t go to therapy but could use some healing, Plevin designed an iPhone game that invites users to build their own digital terrarium. In his research, Peter Kahn, Directory or the Human Interaction With Nature and Technological Systems Lab at the University of Washington and author of Technological Nature, has found that digital nature is not as good as real nature, but it does have some benefits.

So this app isn’t meant to replace nature, but rather to supplement to it. According to eco-psychology, "caring for something, like a pet or a plant, can be healing." And as Jonathan Kaplan, Ph.D. writes in Psychology Today, “Having plants, going for a walk in the park, or even looking at a landscape poster could produce psychological benefits, reduce stress, and improve concentration.” So when a user cares for a digital terrarium, perhaps, they may actually be taking care of themselves. In the app, there are notifications for when the terrarium needs a walk, more sunlight, or simply a rest. "And chances are," Julia argues, "what the terrarium needs is in line with what the user needs."

The work of Peter Kahn demonstrates that digital or technological nature is not as good as the real thing. But it is better than nothing. And in the case of terrariums, Plevin argues, "they are traditionally already behind glass. So putting them under glass—on a screen—is not so very different!"

Soliphilia

The cure to all of this psychoterratic distress, according to the Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht, is soliphilia. Soliphilia is "a state that results in positive energy to come together to collaborate and heal a place, community, and the environment." Plevin was excited to discover through primary research that soliphilia is already happening in some places, including in Gowanus—a micro-neighborhood in South Brooklyn.

Gowanus is infamous for the Gowanus Canal, which between 1915 and 1950 was the busiest commercial canal in the country. It was also the most polluted; factories routinely dumped raw sewage and waste directly into the canal. By the 1950s, the canal was no longer cost-effective, and it essentially became abandoned. But then something interesting happened in this "deserted wasteland": First, artists became attracted to the neighborhood—for the history, sense of "the disgusting," and the large, sunlit lofts. And then groups like The Gowanus Canal Conservancy, and the Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club, started the journey towards soliphilia by restoring and remediating the natural environment of Gowanus.

Plevin conducted a co-creative workshop with local residents on The Whole Foods rooftop to imagine what the future of Gowanus could look like.

Since 2010, the Gowanus Canal has been a Superfund site, and plans are underway for a $500 million cleanup of the canal. Now the neighborhood is in flux: new apartment buildings are being constructed along the banks of the canal, and artists are afraid of being priced out.

While creating a concept map of Gowanus, it became clear to Julia that "community was at the center of everything." And that’s what she found from talking to people as well. As Curtis Cravens from the NYC mayor’s office for Recovery and Resiliency told her, “How do you protect the community? Just as water flows down from Atlantic Avenue, so do people, energy, and ideas.”

Journalist Joseph Alexiou, who is writing a book on the history of Gowanus, also talks about how special Gowanus is. “In Gowanus, there’s a grand opportunity to create a new model for what kinds of businesses can grow in cities in the twenty-first century." Inspired by Alexiou, Plevin conducted a co-creative workshop with local residents on the nearby Whole Foods rooftop to imagine what the future of Gowanus could look like. Participants chose one of four scenarios, and then composed "a postcard from that future." They then created an object that would allow them to connect with nature in that future.

In the end, most of the participants imagined a deeply ecologically-conscious future for Gowanus. As one participant wrote, “Nature can thrive harmoniously if cleanup is paired with the right legislation and planning. Perhaps Gowanus could become an urban oasis of green roofs, waterside trails, and bike paths.”

Cleaning the canal is an example of environmental remediation for a place. Plevin began to wonder what remediation would look like for people. While talking to R.N. and herbalist Marguerite Uhlmann-Bower, she realized that they are actually the same thing. As Uhlmann Bower said, “The plants that remove toxins from our bodies will do the same for soil. I’m positive that there are soil remediators in Gowanus.”

The branding of these objects is decidedly pink and cheerful. This is in complete opposition of the drab and gross Gowanus Canal, and represents the alchemical or magical ability of The Gowanus Outdoors Club to transform a place.

Plevin started sketching out the design for a remediation shop in Gowanus, and the designing tools that would be needed for, perhaps, a wild weed walk—a walking stick, a shovel for digging out weeds, and a small bag for collecting samples. The branding of these objects is decidedly pink and cheerful. This is in complete opposition of the drab and "gross" Gowanus Canal, and represents the alchemical—or magical ability—of The Gowanus Outdoors Club to transform a place.

Re:Store

Re:Store is a three-part service that has a primary goal of connecting the community to urban nature, and a second-order goal of relieving solastalgia. It aims to be remedies for individuals, for community, and for the whole environment. With Re:Store, participants can access their psychoterratic ailment, receive deliveries of remedies, and help rebuild community.

First, Re:ckon is an app that guides users through a ten-minute assessment. At the end of the assessment, they are given an overview of their diagnosis and some recipes and regimens to help them cure. Second, they get the opportunity to sign up for Re:ceive, which delivers soliphilia in "boxed kits" every new moon. Each delivery is different—from a citizen science toolbox to a nature haiku journal; from recipes and ingredients for natural lip balm to a smudge kit.

Third, there’s Re:mediate, a physical place to see soliphilia in action. The first shop is located in Gowanus, immediately adjacent to the Gowanus Canal. There are ecological community events planned, as well as healthy drinks and snacks for sale. There will also be psychoterratic guides on staff, who will lead visitors through an assessment, and help diagnose them with their ailment right on the spot.

The total addressable market for this service is the 50,000,000 Americans who live near Superfund sites, and the target market is the subset of those people who are craving more connection to nature.

Live Prototype of The Gowanus Outdoors Club

In March, Plevin tested these concepts from the Re:Store service in a live prototype of the first remediation shop of the Gowanus Outdoors Club.

The manifestation of The Gowanus Outdoors Club, as an experience, is one of the most high-fidelity, high-resolution products of this thesis. Since the essence of The Gowanus Outdoors Club is about building community, the corresponding experience was an opportunity to get people together in Gowanus to learn about psychoterratic diseases, and then to quickly experience soliphilia.

Guests first made their own trail mix, and were then greeted by "the spirit of soliphilia" before heading out on a scavenger hunt around the Gowanus neighborhood.

The goal of the scavenger hunt was to change people’s perception of a “discarded place.” Guests set out in teams, and had to find their way to 10 different spots in Gowanus. There was a treasure waiting for them at each spot.

Each guest made a terrarium that served as a "visioning tool" for the world they want to create; every ingredient was symbolic. And at the end, the guests took home their terrarium to serve as a reminder of their connection to place and to nature.

As one guest remarked, “It was reassuring to hear that I am not the only one stressing out about the impending doom of the natural world as we know it. My succulent is quite happily keeping me company in my studio now.”

Through this work, Plevin learned that putting a name to these earth-related mental health conditions can help people realize that they are suffering, but that focusing on the cure is what can create change.

Next Steps

Plevin designed a business model to elevate the Gowanus Outdoors Club from a one-time experience to a membership-based urban hangout in Gowanus. It’s a social good model that brings in revenue and gives back to the community. Here, approximately one third of the revenue comes from subscriptions, a third from sales, and a third from corporate events. This model can scale to Superfund Sites across the country by connecting with the community advisory group for each Superfund Site.

Combatting climate change and environmental degradation is more than conserving resources and buying “green” products. It is a matter of expanding the framework to include mental health as well as spiritual and psychological wellbeing.

As more and more people come to realize the detrimental effects of climate change and environmental degradation on our psyche, the way that we frame these issues will change. These are new ways to think and talk about the impacts of global warming.

Up until now, much of the rhetoric and tactics have been focused on getting people to act in order to help the environment. But in fact, their ecological actions will be helping them. As Clive Thompson writes, “Everyone’s worrying about resource management and the spooky, unpredictable changes in the ecosystem. We fret over which areas will get flooded as sea levels rise. We estimate the odds of wars over clean water, and we tally up the species—polar bears, whales, wading birds—that’ll go extinct. But we should be concerned about the huge toll climate change will inflict on our mental health.”

So combatting climate change and environmental degradation is more than conserving resources and buying “green” products. It is a matter of expanding the framework to include mental health as well as spiritual and psychological wellbeing.

For the latest on The Gowanus Outdoors Club and to join future events, visit gowanusoutdoors.club. See more of Julia’s work at juliaplevin.com and contact her at jp[at]juliaplevin.com.