MASTERS THESIS: It's Chinese To Me, by Lusha Huang

Products of Design MFA student Lusha Huang’s master's thesis, It’s Chinese to me: Luck and Cultural Empathy, explores the disconnect between Chinese and American culture. As a Chinese student in an international design department, Lusha enthusiastically took on the role of messenger—eager to share her country’s tradition and philosophy with others. Her over-arching goal is to be part of building a cultural bridge, fostering understanding between Americans and Chinese.

Central to her thesis is the theme of luck, which dates back to ancient China and has always been extremely important to Chinese culture.

Central to her thesis is the theme of luck, which dates back to ancient China and has always been extremely important to Chinese culture. (It is a cultural belief that there are ways of increasing one’s own fortune, prosperity, longevity, and health.)

An amusing take on inter-cultural notions of luck

Lusha created the following light-hearted video to introduce some of the cultural disconnects with respect to the notion of what’s lucky (or unlucky!).

In the video, Rob (an American man) and Kelly (a Chinese woman) experience multiple mishaps because they don’t understand the other’s lucky symbolism. When Rob gives Kelly a birthday gift of four pears, he is unaware that Chinese never give a gift of pears. The reason is that the pronunciation of “pear” (“li”) is the same as the word meaning “to be apart from people and to never see each other again.” Unfamiliar with this, Rob is baffled by her reaction. The number 4, too, is considered extremely unlucky, as it has the same pronunciation as “death.”

In another scenario, Kelly hears about Rob’s recent job interview and wants to wish him good luck by giving him a red pin with the number “six” on it. She chose this pin because in Chinese culture, 6 is a very lucky number. In Mandarin, “six” sounds like the word “flow” and suggests that everything will go very smoothly. But in America, the number 666 is associated with the devil, and much-avoided. Of course, Rob doesn’t appreciate the intention of the gift.

The last scene shows Rob giving Kelly a clock to celebrate her moving into a new apartment. This does not please Kelly, because “clock” in Chinese is “Song Zhong”—which sounds like the phrase that means “to attend a funeral.” As a result, Kelly wants the clock out of sight, but waits until Rob leaves to put it away.

Ignorance of another’s cultural stereotypes, conventions, and beliefs may appear simplistic, but they are examples of how ignorance of another’s culture can create a sense of bafflement and, perhaps, lack of understanding. Lusha set out to create a series of objects that would leverage some of these conventions, using “luck” as her design material.

Lucky #8 Tape

Numbers have always played a significant role in Chinese culture. ‘Ba’ means “fortune.” In Chinese, 8 (or “fa”) is regarded as the luckiest number. Lusha designed sticky tape with the number 8 on it—sure to appeal to Chinese. It’s intended to be used when wrapping gifts, or simply to send a positive message.

Party Cups

For the Chinese, tea is not just a drink, but a concept. Many Chinese believe that when pouring, tea should fill only 70% of the cup—leaving the remaining 30% as “space for your emotions.” Lusha redesigned the iconic American party cup, embossing two words inside it at different levels: one for tea, and one for beer. In the Chinese culture, tea should fill only 70% of a cup, leaving 30% empty. But when pouring beer, on the other hand, the cup should be filled up to the top. With this artifact, the words provide guidance to the appropriate behaviors, and so the cup is appropriate for both beverages.

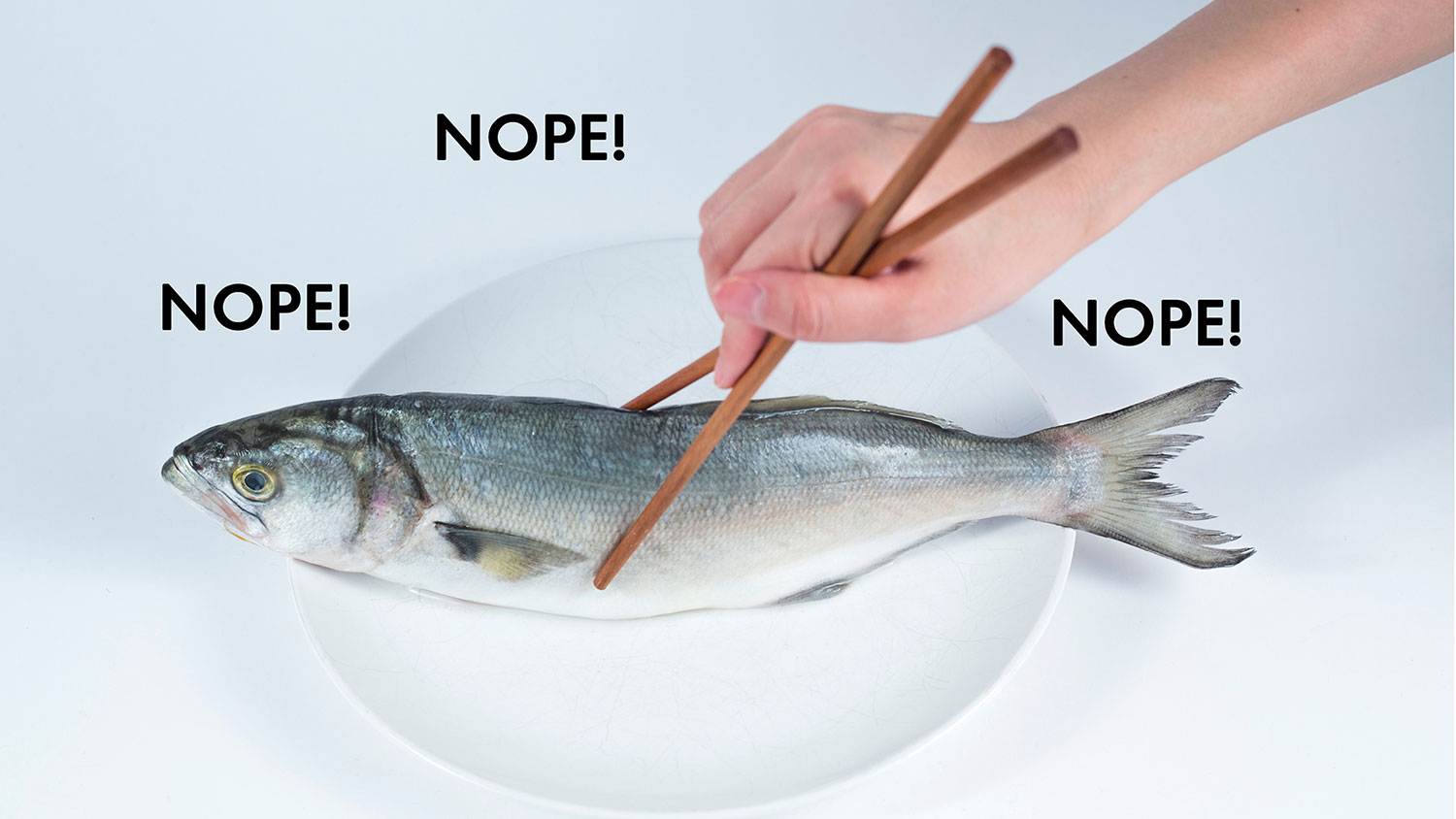

Turning Fish

Here’s another example in the realm of food. In southern China, when people finish eating the upper part of a fish, they do not turn it over. There is a superstition that doing so will cause a fishing boat to capsize in the ocean. Instead, they remove the bone, and eat the other side without turning over the fish. As a little girl, Lusha unknowingly turned a fish over and her mother hit her hand. To insure that this didn’t happen to anyone else, she designed a plate with an alarm that sounds if somebody starts to turn over the fish.

Chinese Lucky Clinic

The Chinatown neighborhood in New York City is home to the largest enclave of Chinese in the western hemisphere. It is an extremely vibrant place, with many shops selling Chinese lucky objects, and where each item is thought to have a specific lucky function.

Lusha used the practice of Chinese palm reading as an ideal gateway to the experience; it’s interactive, and quickly attracts an audience.

For the next work, Lusha wanted to move beyond the simple artifact and create compelling experiences that involve multiple senses. She set out to find ways of communicating to shoppers which specific items might address their particular needs. She had seen that shopkeepers—afraid of appearing pushy—didn’t approach customers, leaving them uninformed. Lusha saw this as a potent design opportunity.

Lusha created tags with information to accompany the items in order to educate shoppers. In conjunction with the Harmony Gift Center located at 63 Bayard Street—which sells Buddhist statues and other ritual objects—she conducted the “Chinese Lucky Clinic.” Owner Ben Chen cooperated with her efforts, letting her use his shop and providing guidance along the way.

Lusha used the practice of Chinese palm reading as an ideal gateway to the experience; it’s interactive, and quickly attracts an audience. She provided readings free of charge, using her iPad to scan a hand with left from the app “Chinese Palm Reader.” She began by drawing the lines of their hands on her iPad accompanied by an intriguing sound. When the scanning was complete, the app began its analysis.

The Line of Fate tells the importance of a career in a person’s life, the Line of Heart addresses the emotional component, and the Line of the Head relates to intellectual capacity. Following the analysis, and acting as the “prescriber of good fortune,” Lusha wrote a prescription based on the results of the palm reading. The subjects, if they chose to, could then purchase a charm or other object associated with what was said to be lucky for that individual.

The example shown below is Steven, whose palm reading result was the following; “You are a person who must think long and hard before you start something.” Lusha checked the box showing a lion head—the symbol believed to bring luck and depict bravery—which would be useful for his upcoming adventure.

Both Chinese and non-Chinese participants found this experience to be a lot of fun. And as a result of the exercise, those new to the Chinese traditions could now begin to distinguish between the many items available in the store.

If they made a purchase, Lusha gave them a small palm necklace in the shape of a hand, constructed of colorful acrylic which she designed. Palm lines are continually changing, and here the customers would have a guide, instructing them to smile more, perhaps, or to complain less, or to buy a specific lucky object. Wearing the necklace, they were able to see—by the way the lines moved—if luck came their way. The game was fun, original, and very Chinese!

Chinese are in the habit of sharing dishes, but Americans generally order individually.

This created excitement and got people interested in finding out more about Chinese traditions. Understanding what various objects symbolized gave them reasons to purchase a souvenir. And even those who didn’t subscribe to the beliefs were intrigued by the adventure. One American, curious about his romantic pursuits, summed it up his experience by saying, “If I have a lot of gods to protect me and bring me luck, no one will reject me, right?” And even if participants chose not to purchase anything at all, they nevertheless came away with a better understanding of what they were looking during their tour of Chinatown.

Co-Creative Workshop

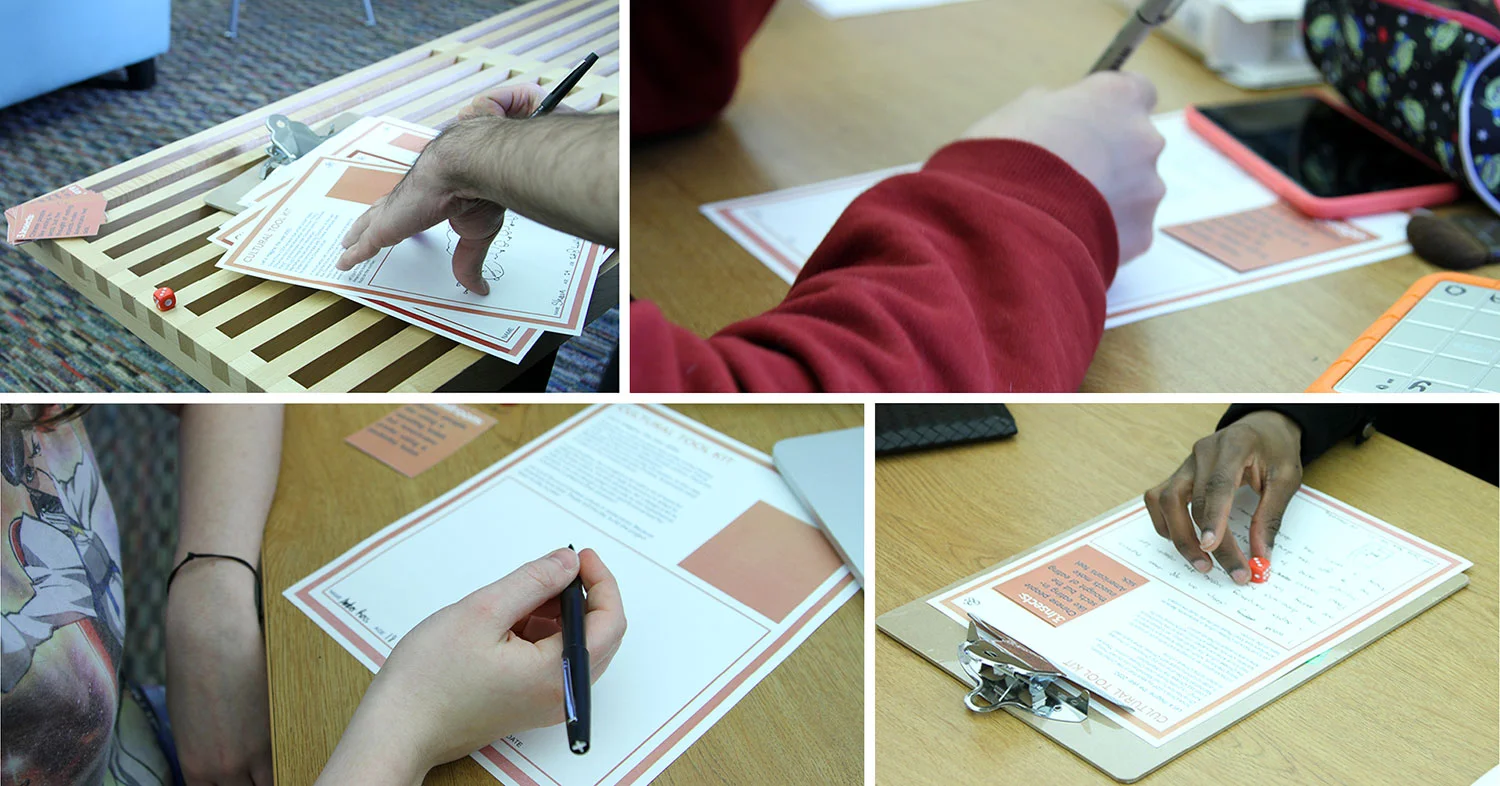

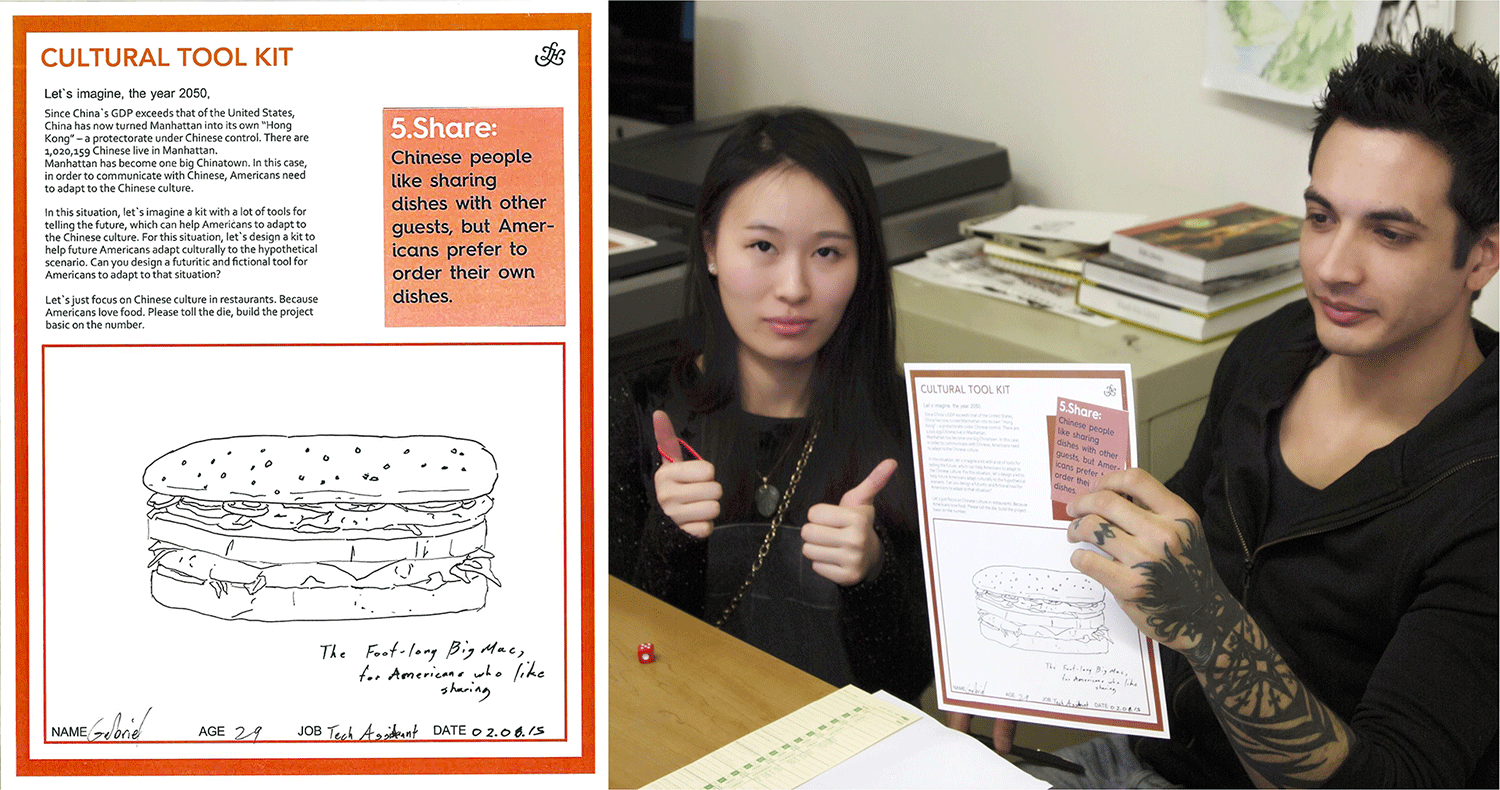

Two weeks later, Lusha held a co-creative workshop, assembling a group that would generate new ideas within the scope of her project. She pointed out to them that with over a million Chinese living in Manhattan, the city could be said to be a “mini Hong Kong.” With that in mind, the group was asked to design a kit hat would help Americans adapt to the rising number of Chinese living among them.

She presented the group with a hypothetical scenario, and challenged them to conceive of a futuristic tool. The fantasy year chosen for this project was 2050, with China’s GDP exceeding that of the United States, and Manhattan now another Hong Kong—a protectorate under Chinese control. There would be 1,020,159 Chinese living in Manhattan, making the city one big Chinatown. In this scenario, Americans would have even more reason to understand the Chinese lifestyle.

Observing how much Americans love food, Lusha designed a game to compare Chinese and American habits with a particular emphasis on eating in restaurants. She associated particular aspects of eating with numbers on the die and had each person roll the die to determine which aspect they would be addressing.

Drinking: Chinese like drinking hot water, but Americans prefer water with ice.

Restroom: Chinese are fine using a squatting toilet, but Americans choose pedestal toilets.

Insects: Chinese eat insects, an idea that repels most Americans.

Atmosphere: Chinese talk loudly in restaurants and enjoy a lively environment. Most Americans, particularly older ones, prefer a quieter, more serene setting.

Eating: Chinese are in the habit of sharing dishes, but Americans generally order individually.

Language: Many Chinese know English, but it’s rare for an American to speak or read Chinese.

The participants of the workshop—held in the school library—were students attending the School of Visual Arts with different majors.

Gabriel, a tech assistant at the library, rolled the die and got Eating as his subject. He designed an oversized (foot-sized) hamburger to inspire Americans to follow the Chinese custom of sharing food with others.

Yiyi Shao, a graphic design major student, drew Language. Recognizing the difficulty Americans may have when ordering from a menu, she proposed a device that scans pictures from a menu and shows illustrations with ingredients listed in both Chinese and English. (An added feature imagines the device releasing a corresponding scent so Americans will know whether or not they might like it.)

Chloe Ginex, an animation design major student, drew Restroom. She designed an inflatable, plastic cushion that Americans can use to transform a squatting toilet into one that allows for sitting. It can be deflated and stored. (And hopefully cleaned!)

Amber Pwss, an animation design major student, also drew Restroom, and thought of something similar to a baby-bouncer that would suspend the wearer while using the toilet.

Shawn, a resident assistant at the Ludlow Dormitory, drew Insects, and designed a giant, cute colorful gummy bug to encourage Americans to feel more positively towards bugs.

Dozie Kaw, a creative designer, also drew Insects and chose to create an app that explains the nutritional value of insects and makes the point that many foods are an acquired taste.

Pizza Plate

As mentioned above, luck and sharing with others are extremely significant to the Chinese. Sharing food is perceived as caring and considerate—as a way of promoting harmony between people. This is very different from how Americans primarily eat out, which is largely ordering individually. The exception here is pizza.

To help Americans adapt to the concept of sharing food, Lusha designed “a gateway culture adaptor” with pizza integrated into the concept. On a large, round pizza plate is the pizza base. The individual orders, such as steak, chicken, spaghetti and fish, are distributed on each section of the plate.

NiHow

Interaction between China and America is always increasing. China is one of the largest trading partners of the United States. Lusha obtained some statistics when visiting the China National Tourist Office in New York

• In 2012, China-US trade reached $484.7 billion.

• In 2013, 2 million Americans visited China.

• The number of American visitors to China has increased by 60% over the past eight years.

When considering international travel, Lusha wanted to use design to familiarize travelers with her country’s customs and people—both to encourage more interaction and to make them more comfortable in China. She designed NiHow, a “cultural training” app designed to introduce the Chinese lifestyle to Americans. It clarifies customs and eliminates some common misconceptions. The app is useful to Americans traveling to China, as well as to teachers and students interacting in classrooms with students from China.

That Lusha is familiar with design in both countries helped her create a program that can be easily understood. Her technology advisor on the project was Kyle Yu, originally from Hong Kong and a software engineer who worked at Shapeways, NBC, and other companies based in New York City.

[Insert starbucks+app notification_Huang_1920 here]

NiHow users can download the app the prior to visiting China, choosing which themes they want to learn about from the following six: Shopping, Living, Transportation, Entertainment, Eating and Places.

Nihow uses Geo location to help Americans learn about Chinese culture and etiquette, giving them tips according to where they are and what they are doing. And it is able to provide the equivalent information in the other country. For example, if a user is near a Starbucks in New York, the app will send a notification about Chinese tea etiquette (tea having the stature that coffee enjoys in America). The notification sent by Nihow, when clicked, is enlarged to provide more detailed information. And once an American is better informed, he or she can start practicing what they know. (An example would be that Nihow informs the user that in China, tea is served first to others.) The app also lets Americans connect with other users, and directs them to relevant companies.

Lusha plans to partner with the China National Tourist New York office (CNTO), a non-profit organization whose goal is to promote travel to China. She is hopeful that they will provide her funding for further development. Additionally, she will work in conjunction with travel agencies, airlines and local restaurants to help market the platform.

One of her test users, Hovey Brock, was enthusiastic, exclaiming, “I will totally use this! Americans are big on sharing. I would love to see information coming from actual people and not from companies.”

Lusha hopes that the work created during her thesis demonstrates that design can play a huge role in constructing bridges between cultures, and that humor can lead the way.

Read more about the project, including subject matter experts and research protocols, in the PDF above. Email Lusha Huang at lusha[at]lusha-huang[dot]com.